Black and White Magazine can be purchased at https://www.bandwmag.com

THE PEOPLE THAT TIME FORGOT

Oliver Klink’s exploration of ancient cultures in Asia captures the eternal grace that endures against the relentless sweep of modernity.

Oliver Klink would never forget the proverb his father-in-law told him during his first trip to China: “When you cross the river, you need to feel the pebble under your feet.”

Klink had married a first-generation Chinese-American woman, and he had traveled with her and her parents back to their home country. It was the first time Klink’s father-in-law had returned to China since they had left in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution. The older manhardly recognizes the new China, its densely populated urban expanse clogged with skyscrapers and cars, air thick with pollutants, masses of people walking with heads bowed to smartphone screens.

“My father-in-law thought that China grew way too fast,” says Klink. “He told me I would have to travel further beyond the cities to see the real China.”

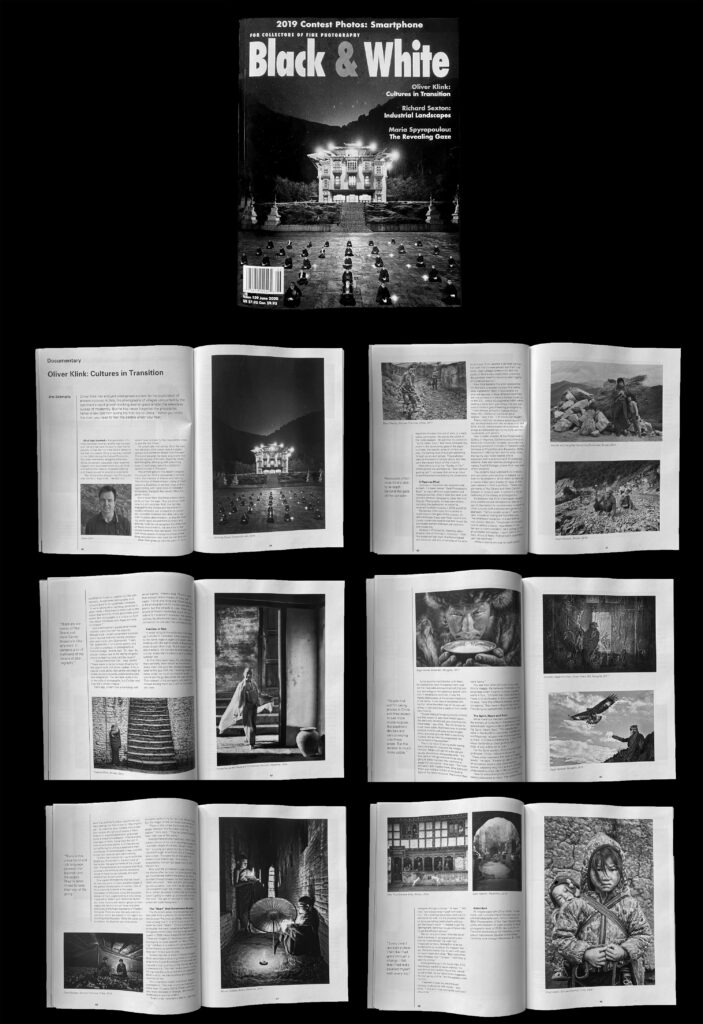

He would take that advice. Over the next two decades, Klink would carry his digital camera and penetrate deeper into Western China and beyond. He made excursions into remote regions of Bhutan, Myanmar, India, and Mongolia, emerging with a stunning body of work organized in a collection called Cultures in Transition.

This almost generic title doesn’t prepare the viewer for Klink’s transcendent achievement, the mastery of shadow and framing. The intimacy of these images, many of them capturing Buddhists in somber ritual and villagers toiling with rustic tools in forbidden landscapes, transport the viewer into a forgotten world.

But it never feels like these photos beckon to us from the past. They are of our own time but still separate. Both the families engaged in rote chores and the monks in mindful reflection are steeped in centuries-old, inviolable traditions that they carry out with ritualistic determination, as the developing world rages around them in chaos and disarray. Even as we recognize the alienness of these environments, we are alive to the shared humanity they represent. We connect with these people in recognition that something very precious may soon be lost forever.

What Klink gives us with his work is not a depiction of a lost tribe out of time or a backwards community. He rejects the cliché of the noble peasant. He subtitles his collection, “Spirit, Heart, Soul,” and these concepts resonate in the penetrating gaze of the eagle huntress, the beatific smile of children at play, the bathing rays of sunlight cascading through an ancient temple. These photos capture moments of simple labors, but they carry the vibrant thrum of the uncanny.

Klink refers to it as the “fluidity of life,” where people are animated by “their spiritual guiding light”—phrases that come as close to anything else in describing the unnamable.

A Rigorous Mind

Cultures in Transitionhas received wide acclaim. It’s been named “Best Photography Book” by eight different organizations and media properties. Klink’s work has been published in National Geographic, Daily Mail, Popular Photography, among many others, including this publication. In 2016 and 2018, he received the Spotlight Award by Black and White Magazine.

Reviewers often note Klink’s ability to reach beyond the gaze of the outsider, to demythologize these rural Asian regions to create immersive experiences that reveal the permeable borders between old traditions and modernity.

Writing in Photolucida, Drazenka Jalsic Ernecic says of Cultures in Transition: “With the sustained high level of anthropological and historical skill and universality of his artistic concept, Klink reaches a spiritual connection with the Chinese people and their customs. Clear vintage composition and the purity of Klink’s new modernism underline the common need for humanity and fragility of human existence.”

How Klink became the artist responsible for this work is another mystery that defies easy explanation. Born in Switzerland, he earned degrees in three different countries, earning a masters in physics before traveling to the U.S., where he acquired an MBA while landing a job at tech giant Cisco. He also pursued a lifetime goal of learning photography.

“I took classes at Foothill College but never got a degree,” says Klink. “I’m mostly self-taught,”

Many creatives harness a gnawing anxiety, an impatience with the world as it is. Not Klink. As you would expect of a physicist, he brings a methodical rigor to his craft, combining tenacity with artistry.

Geir Jordahl, director of the PhotoCentral Gallery in Hayward, Calif., has been friends with Klink for more than 15 years, launched the traveling exhibit of Cultures in Transitionand the book at PhotoCentral in December 2018. Founded in 1983 by Geir and his wife, Kate, the facility also holds classes and is equipped with a darkroom and 10 enlarging stations. Kate also teaches photography at nearby Foothill College, where Klink was one of her students.

The Jordahls have watched Klink’s talent and reputation grow as they’ve helped nurture his development. (Klink refers to Geir as a mentor.) Geir says that he sees shades of many of the past masters in Klink’s portfolio. “There are elements of Paul Strand and Henri Cartier-Bresson in Oliver’s work. It contains a lot of hallmarks of the history of photography.”

He believes that Klink’s immigrant experience and his natural introspective nature is part of the reason he can immerse himself in other cultures with a curious and generous approach.

“He’s a people person,” says Jordahl, himself an immigrant from Norway. “He embraces humanity—it’s something that comes naturally. The people he encounters in various cultures, regardless of the barriers to communication, he’s going to find an authentic connection. I don’t care if it’s Asia, Africa, or Mars. That genuine openness can’t be contrived.”

While it seems unusual for a physicist and MBA to master a creative skill like photography, Jordahl sees photography as a uniquely good fit for systematic mindsets.

“If we’re talking about painting, sculpture, or other media, I think there’s more truth to the notion that scientific minds don’t make good artists. But photography is a unique art form that allows individuals with these skillsets to blossom.”

Klink’s achievement speaks of an innate visionary talent that can’t be acquired through study. Jordahl remembers a conversation he once had with the late photographer and curator John Szarkowski.

“I said, ‘Mr. Szarkowski, I run a photo gallery, but my wife’s a professor of photography at Foothill college.’ And he said, ‘Oh, dear. So should I write a note to her saying, congratulations on teaching what can’t be taught?’

“I always remember that,” continues Jordahl. “There needs to be some type of calling for the type of work that Oliver creates. If not a natural innate ability, then at the very least an innate proclivitytowards understanding light and composition. You can learn quite a few of the skills of photography, but it’s that next step that’s almost magical.”

Years ago, Jordahl took a workshop with Ansel Adams.

“Adams said, ‘There’s more than enough sharp images of fuzzy concepts.’ I think one thing that Oliver has done in his photography is to create work that is poetic but the veracity is clear. It has the traditions of historic reportage, but it fits outside of it. He doesn’t represent his subject as victims; he empowers them. He creates a connection to cultures that are not his own.”

Families at Risk

In order to build the collection that made up Cultures in Transition, Klink would return to the same regions again and again, communicating with the same locals in these remote areas to gain their trust. But it wasn’t just about access. He wanted to understand their culture, share their traditions as much as an outsider can.

At first they were wary. He would take their portraits, then return to the area to share them. He said the residents became used to the guy with the “bobbing head” and ready smile, so much so that the locals would ask his guides when he was returning. They relaxed in his company, and soon he moved among them as if part of their everyday lives.

As he become more familiar with them, he realized that what threatened them was not the inexorable encroachment of 21stcentury technology or the rapacious growth common in developing countries. It was the steady deterioration of an ancient institution of the family. It was loss of emotional connection. More than their way of life was vanishing—it felt more like a piece of their world was missing.

“People find out I’m taking photos in China and they expect to see more modernization, the electronic devices and cars crowding into these areas,” says Klink. “But the tension is much more subtle. Everybody lives in a small physical location with easy access to each other, and what grounds them is the family nucleus. But as time has progressed, the family nucleus has exploded.”

This is the result of young adults leaving the rural areas for cities and the modern lifestyle. What’s left behind is the old and young, the children and grandparents.

“It’s two parts of the generational divide struggling to either maintain their traditions or adopt the new world,” he says. “The modernization didn’t bother them. What bothered them was losing a little bit of the guiding light of the family structure. That’s what they were losing.”

You see how often children factor into Klink’s images. He believes that was to his advantage when it came to capturing this world in flux.

“Children are more authentic. There is no artificiality in their movements,” he says. “And this effect is shared, almost contagious. They have a disarming effect. They bring out authenticity in adults as well.”

The Spirit, Heart, & Soul

While there’s a thematic commonality to the entirety of Cultures in Transitions, Klink labeled each region under a different heading: Spirit, Heart, and Soul.

“The people that were in the Buddhist countries, like Bhutan and Myanmar, religion was more important to them. In China and Mongolia it was more about the family as their guiding light. In India, it was a little bit of both.”

For the Spirit section, he concentrated on Bhutan, China, India, and Myanmar.

“These areas represent the spirit of village bonds,” he says. “People go about their way on unmarked streets and unnumbered homes, speaking very little to each other but understanding their role in the community.”

Here he encountered monks and their careful adherence to ritual. The solemn reverence that attends Buddhist ceremonies are ideal settings for Klink’s talents. In “Morning Ritual,” an unearthly glow radiates from a massive temple, as a group of monks in black roles sit in a perfect geometric grid enraptured in prayerful meditation. A flame alights near each of them. Some hold the light in their outstretched palms, as if they are nurturing the soul’s luminous essence in their very hands. It’s a remarkable image, one that brings new rewards upon each viewing.

To Klink, the mystical isn’t confined to the Buddhists. It’s evident in the bent back of the farmer, the gnarled hands of the ploughman. The ceremonies and customs that have survived since antiquity are the connective tissue of these insular cultures, and each moment has its own power.

One aspect of modernity that has found its way into some of these ancient villages is the gradual emancipation of women. One of Klink’s favorite subjects is the eagle huntresses of Mongolia. Long the exclusive domain of men, eagle hunting is now being mastered by Kazakh girls. Known as Burkitshi, these hunters don leather gloves to train eagles and falcons to hunt foxes and other small prey in the frigid mountains of Western Mongolia. There are also festivals and competitions, which are popular in the region surrounding Altai Mountain.

While the hunts can be violent, the Burkitshi are more accustomed to performing for tourists these days. But the magic of the old ways still remains.

“There is this unreal bond and rich language between the Burkitshi and the eagles. They’re determined to keep their way of life going.”

Klink befriended one huntress, who’s the subject of one of his most bracing images, “Aimuldir—Eagle Huntress—Seven Years Old.” A young girl gazes fondly at her falcon as we watch through what looks like a flowered, lace curtain. The serenity of the setting speaks to an Edenic age, to a world unspoiled by the corrupt appetites of the modern era.

Klink said the girl asked to see more of his photos after he took the photograph. She sat mesmerized before his laptop as they scrolled through images he had taken on his latest excursions. “She had this strong energy and curiosity. I sat with her all night as we looked through the photos,” remembers Klink.

When he asked if she was worried she wasn’t going to wake up in time for school, she said, “We get an excuse to miss class when we meet foreigners.”

The “Heart” that Sometimes Breaks

The Burkitshi series shares similar qualities with Klink’s photos from his travels in the Sichuan Province of China. where he lived among the Yi. It is Yi’s section of the book he titled “Heart.” This is where you encounter the hard, weathered faces of a struggling community that survived an earthquake in 2008, which killed 69,000 people. These are images of hardship and scarcity, but dignity is never absent. In “Boys Playing,” children in a makeshift wheelbarrow prove there’s no environment so barren that they can’t find a way to play.

Sometimes life is short in these villages. Klink remembers returning once to a remote area in the Fujian Province of China and sharing with a man a photo of his family taken on a previous trip. The man broke down crying. He had lost his wife in the interim between Klink’s visits. He had no other photographic memory of her.

Klink cherishes these moments, these connections. This was a long-term project, more than 15 years. While these communities resist decades of change, the interior landscape is another matter.

“Every time I revisited a place, I felt like I had gone through a change,” he says. “I felt that I had rediscovered myself with every trip.”

His numerous excursions were also in service to his craft. It’s the physicist’s habit of doing something methodically until you get the elegant result.

“I needed to get the lighting right, learn how to use different inks to get the effects I wanted.”

The son of a printmaker, Klink has developed a process of using piezography inks that he mixes himself. He uses high megapixel cameras, finding film to be too burdensome to handle on his frequent travels. While he knows how to work with color, he favors black and white.

“Black and white has a timeless feel,” he says. “I don’t like to date my photos.”

Since growing up in the Swiss Alps, Klink has always wanted to be an explorer. His wanderlust and curiosity found their natural outlet in Asia. As his father-in-law suggested, he kept going until he “felt the pebbles under his feet.”

“I learned to lose my preconceived notions, to dispense with clichés,” says Klink. “I felt as if I was seeing the world as it should be.”

Published in Black and White Magazine (March 2020)

Additional resources to make Black and White Images:

**** Pixpa: Top 10 Tips for Black and White Photography and Portraits

The proud owner of two copies of Cultures in Transition, I have not yet seen the images as published in Black and White Magazine. I am nevertheless delighted to discover here that the master craftsman and artist Oliver Klink continues to receive much deserved and hard earned accolades for his exquisitely composed and meticulously detailed work. The text of the article includes not only intriguing details of the background behind the 15-year project, but also shares intimate moments of Oliver’s particular encounters with the inhabitants of his images. The inclusion of Geir Nordahl’s fascinating quotes gathered during a life in photography along with a few enticing technical details round out an article that will interest anyone with a serious interest in the making of fine art photographic imagery. Can’t wait to have the March issue of Black and White Magazine in my hands.

An outstanding article that illuminates this amazing work — and especially its maker — to a much deeper level than I realized previously. It’s not my first encounter with the work or the story, but I feel like this article peels away a deep layer of the onion skin. Go Oliver!